For snowboarder Spencer O’Brien, breaking trail in the backcountry with the support of peers like skier Tatum Monod has shown her a completely new side of the sport — and herself.

IMAGES: JESSY BRAIDWOOD | WORDS: JEN ATOR

It’s a crisp, bluebird day, and Arc’teryx athletes Spencer O’Brien and Tatum Monod are touring in the Tantalus range outside Whistler, Canada. Joined by a local guide, the women are hoping to get on some big lines, but the mountain has other plans.

“Sometimes you head out with a certain objective, but the mountains tell you no,” Spencer says. “And you can’t get mad at that. You have to learn to silence your ego and be able to listen.”

That’s the deal you make when you leave groomed lines for unmarked terrain. Some days, you’ll spend hours in a skin track to only score a few short turns. Other days, you might not even be that lucky. Cultivating a patience and perspective to not be put out by that reality does not come naturally for some.

It certainly didn’t for Spencer.

“The biggest wakeup call when you come from resort riding or the competition arena into the backcountry is how little you actually get to do the sport,” she explains. “So much of your day is dedicated to getting to something, setting it up, and assessing the conditions. It’s been very hard for me to learn how to slow down and be flexible, because that’s not how I used to snowboard…at all.”

Peak Pursuits

Following in her older sister’s footsteps, Spencer first learned to ride at 11 years old and turned pro just five years later. With a fearless appetite for hitting big features and even bigger air, the two-time World Champion, two-time Olympian, and X-Games gold medalist is considered one of the world’s most progressive slopestyle snowboarders of her time.

For the better part of 36 years, Spencer’s view of snowboarding existed within an intense, fast-paced pressure cooker. Singularly focused and admittedly selfish, every detail was dialed from the moment she woke up to the moment she dropped in. Confidence was gained through repetition, and competence compounded season after season.

When she closed the book on her competitive life, she announced a pivot: She would be taking her talents into the backcountry. To the unacquainted, that transition may not sound all that drastic. After all, she was a professional snowboarder. How different could backcountry riding really be?

“Nothing kicks my ass quite like touring,” Spencer says with a laugh. “That’s especially humbling when you consider yourself a pretty strong athlete. There have been moments where I’ve been completely and utterly put in my place.”

Nothing kicks my ass quite like touring....There have been moments

when I’ve been completely and utterly

put in my place.

Nothing kicks my ass quite like touring....There have been moments

when I’ve been completely and utterly

put in my place.

While competition runs are planned and predictable, the mountains are…anything but. Even classic, well-known backcountry spots that Spencer goes to a lot — they never form the same way twice. Sometimes the snowpack is different; sometimes they don’t form at all, they’re just not hittable. You really never know what you’ll be riding until you’re there.

“That’s something I’ve struggled with, because in competition there’s so much repetition, and in the backcountry you don’t get that,” she says. “I still hesitate a lot—especially with line riding. Seeing people like Tatum who can see a line and ride it like they’ve ridden it eight times already is super inspiring.”

It’s not that Tatum’s a natural-born savant. OK, maybe she is. She was the first woman to stomp a double backflip on skis in the backcountry, and she’s spent more than a decade taking on the steepest lines and biggest spines with her playful-yet-powerful style. At 32 years old, the professional freestyle skier has already sealed her spot among the greats.

But it’s more that Tatum’s time in the backcountry has taught her how to adapt. “There are so many things that we do before we’re standing on top of our lines for the first time,” she says. “For me personally, I study the face. If I’m touring, the whole time I’m just looking at the line, visualizing myself riding it as many times as I can. So by the time you’re standing up there, you know your landmarks. You can relax and have fun with it, because you know you’re prepared. That’s where I ski my best: When I think, I’m going to flow this thing so hard because I know it like the back of my hand.”

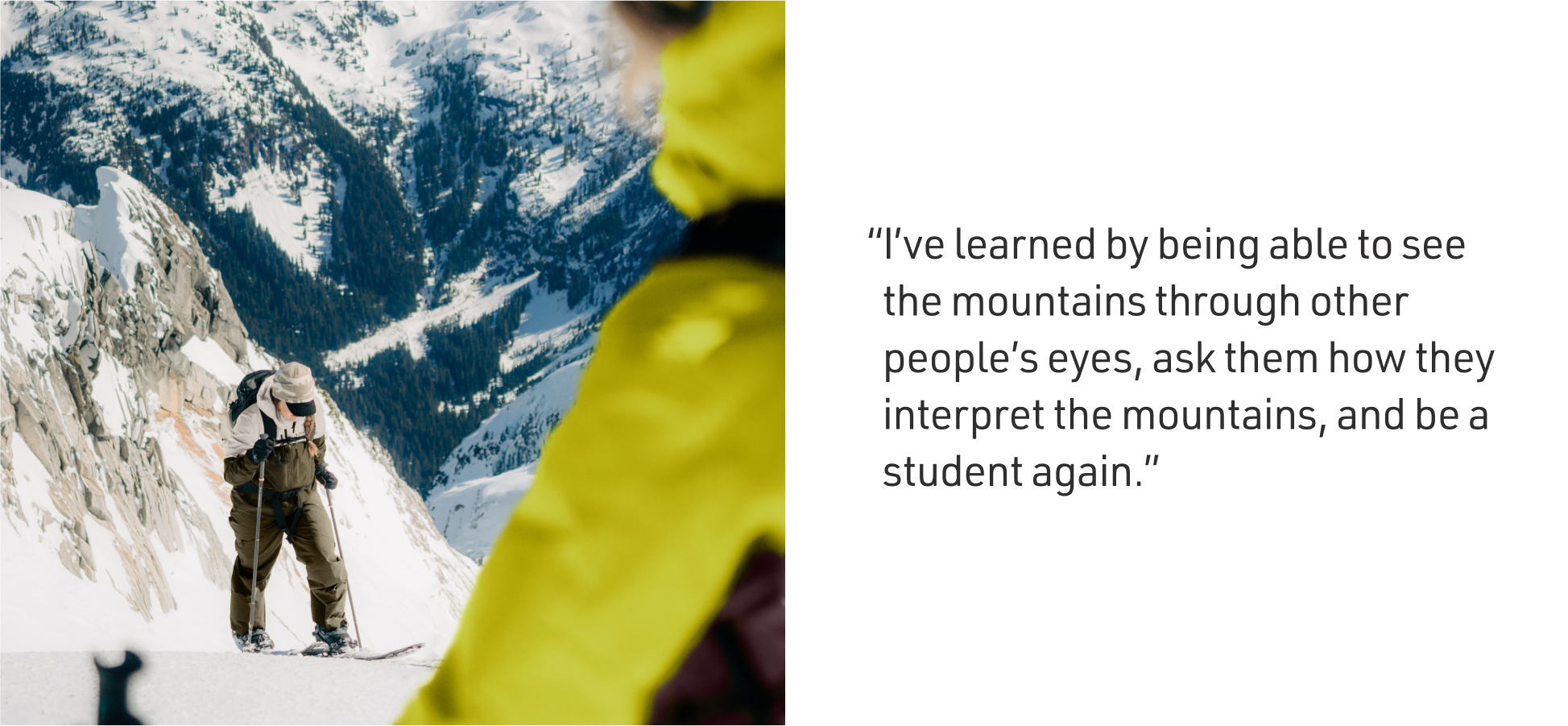

That perspective has helped Spencer come to appreciate the slow pace of skinning, utilizing that time to absorb as much as she can from the mountain — and her peers. “That’s really how I’ve learned,” she says. “Being able to see the mountains through other people’s eyes, being able to ask them how they interpret the mountains, being able to be a student again. It’s so important.”

Winning, Reimagined

Asking for help, being vulnerable — it might be what’s needed to grow and learn, but that doesn’t always make it easy for the fiercely competitive and accomplished. Whether by nature or nurture, there’s a distinct intensity and acknowledged stubbornness that tends to accumulate in the athletes who have touched the proverbial mountaintop of their sport.

It’s something these two women share. “Spence and I have similar personalities where we both really want to do things the best we can, and we get angry with ourselves if we’re not,” says Tatum.

“I’ve seen this with you a couple of times, Spence,” she says to her friend. “You’ll be hitting something and not landing, and this fire in you starts growing. I’m the same way. In the early days, I’d be so frustrated when I couldn’t keep up, and it would be really hard not to show that.”

Harnessing that fire is crucial; being able to tap into that intensity is what helps you grow as an athlete. But Tatum has also seen that when the fire is neglected and unmanaged, you get burned.

“The self-talk that used to go on in my head I would not say to my worst enemy,” she recalls. “That used to be how I fueled myself, and I really had to work to remove that poisonous aspect. I still have that fire, but once I learned how to bring more positivity in, it took a pressure off my shoulders and opened up a freedom within my skiing.”

“That’s been the constant in my athletic career, learning how to channel that part of yourself that’s very driven and aggressive,” Spencer admits. “As a competitive rider, I was very structured and rigid. My self-talk would be that way, too. I felt like I needed that pressure to be able to perform, and I would beat myself up before, during, and after it if it wasn’t perfect.”

It’s understandable. When you turn a passion into a profession, there’s a pressure deep down that creeps up, Tatum says. But that’s why it’s so important to know what you’re really chasing. “Sometimes I have to remind myself that I’m out here having fun, and I would be doing this regardless of any outside pressure. Ultimately, our goal is to inspire people. I want people to watch me ride and think, That looks really fun.”

As a competitive rider, I was very structured and rigid....I would beat myself up before, during, and after it if it wasn't perfect.

As a competitive rider, I was very structured and rigid....I would beat myself up before, during, and after it if it wasn't perfect.

After a lifetime of chasing medals, it can be unsettling to a professional athlete when they no longer feel the same drive to compete. When they’re out there “just for fun.” But Spencer is slowly realizing that in her case, it’s not a sign of atrophy. It’s growth.

“The Olympics were a big ego feed. You feel really big when you compete and when you’re doing well,” she admits. “I have a lot of appreciation and love for that part of my career, but it feels really nice to let that go and to get those incredible feelings of accomplishment and joy in a different way.”

Five years ago, days like this one — crap snow, no big tricks or monster runs — might have felt like a disappointment. But Spencer sees the joy that Tatum brings to the backcountry, and in it she’s starting to see a new line for herself. One that’s no less intense or ambitious, but merely removed of extreme highs and lows. One that’s fueled by genuine stoke and gratitude, not gripped by pressure and expectation. One that’s not pursued for perfection, but embraced with curiosity.

“I’ve always loved the mountains, but when I competed, I didn’t appreciate them as much,” Spencer says. “I could spend the rest of my life learning about them and still have so much left to learn. That relationship, and the one I have with people who also get it, has been the biggest gift.”