Seasoned climbers Will Gadd and Sarah Hueniken reflect on their relationship to one of climbing’s most important, and difficult, themes.

IMAGES: JOHN PRICE + ANGELA PERCIVAL | WORDS: ANDREW BISHARAT

The cool alpine air whipped across the blue limestone face of Waskahigan Watchi, also known as Mount Rundle, in Canmore, Alberta. Sarah Hueniken and Will Gadd were several hundred feet up a route called The Alt Left, a relatively new 5.12 multipitch that’s been dubbed the best “locals’ big wall.” As a married climbing-guide couple, Will and Sarah were having a moment of professional disagreement.

“Hey, that setup isn’t ideal for me. Can you fix it?” Sarah asked.

“There’s no way that knot’s gonna roll,” Will responded.

“Yeah, but I don’t like how much tail there is,” she countered.

“What’re you talking about? It’s totally fine. It’s bomber!”

“Just fix it. Please.”

On multipitch climbs, there are a hundred ways to build safe anchors. Yet you’ll always find a lot of contention, especially among professional mountain guides such as Will and Sarah, over what’s “good” and what’s “good enough.”

With their decades of experience, you might not expect an exchange such as this, especially over something as basic as tying a knot.

But in climbing, the consequences of our decisions, even the most seemingly minor ones, can be massive. And our perceptions of risk can be subjective, either giving us a false sense of security or filling us with irrational fear—and everything in between.

Will let out a little grunt, but then fixed his knot as Sarah had asked. Then, he says, he was immediately filled with disappointment in himself for rolling his eyes at his partner’s request. Communication is foundational to managing risk in alpine environments. The fact that climbing typically involves two people means that good communication skills are central to staying safe on any ascent.

“It’s super crucial to speak up,” says Sarah. “Even a beginner climber can catch a mistake. We all get habitual. And it’s always worth taking a pause to discuss something. That 15 to 30 seconds won’t make or break your day.”

For Will and Sarah, having both lost close friends in the mountains in recent years, they believe that climbers could do more to consider their relationship to risk — beginning with a humble understanding of what we can, and can’t, control.

Even a beginner climber can catch a mistake. We all get habitual. And it's always worth taking a pause to discuss something. That 15 to 30 seconds won't make or break your day.

Even a beginner climber can catch a mistake. We all get habitual. And it's always worth taking a pause to discuss something. That 15 to 30 seconds won't make or break your day.

Deconstructing Risk

Risk is commonly defined as taking an action in which there lies the possibility of something undesirable happening. To take a risk, there must be uncertainty and a probability that a negative consequence could occur.

What that probability actually is — especially in high entropy areas such as big, snowy mountains — is where it gets tricky.

Will is widely considered one of the best ice and mixed climbers of all time. He’s responsible for establishing the super futuristic overhanging ice climbs of Helmcken Falls, and making a rare first ascent of a frozen Niagara Falls, among hundreds of other hard winter routes.

Will is currently working on a book about risk. He gives talks at various conferences and corporate events on the topic. As part of this work, he’s studied the way industries assess risk in their fields. He’s seen the depth of analysis they provide to support their decision making. To him, as a longtime climber, paraglider, and kayaker, these analyses highlight just how crude much of our calculations as mountain athletes truly are.

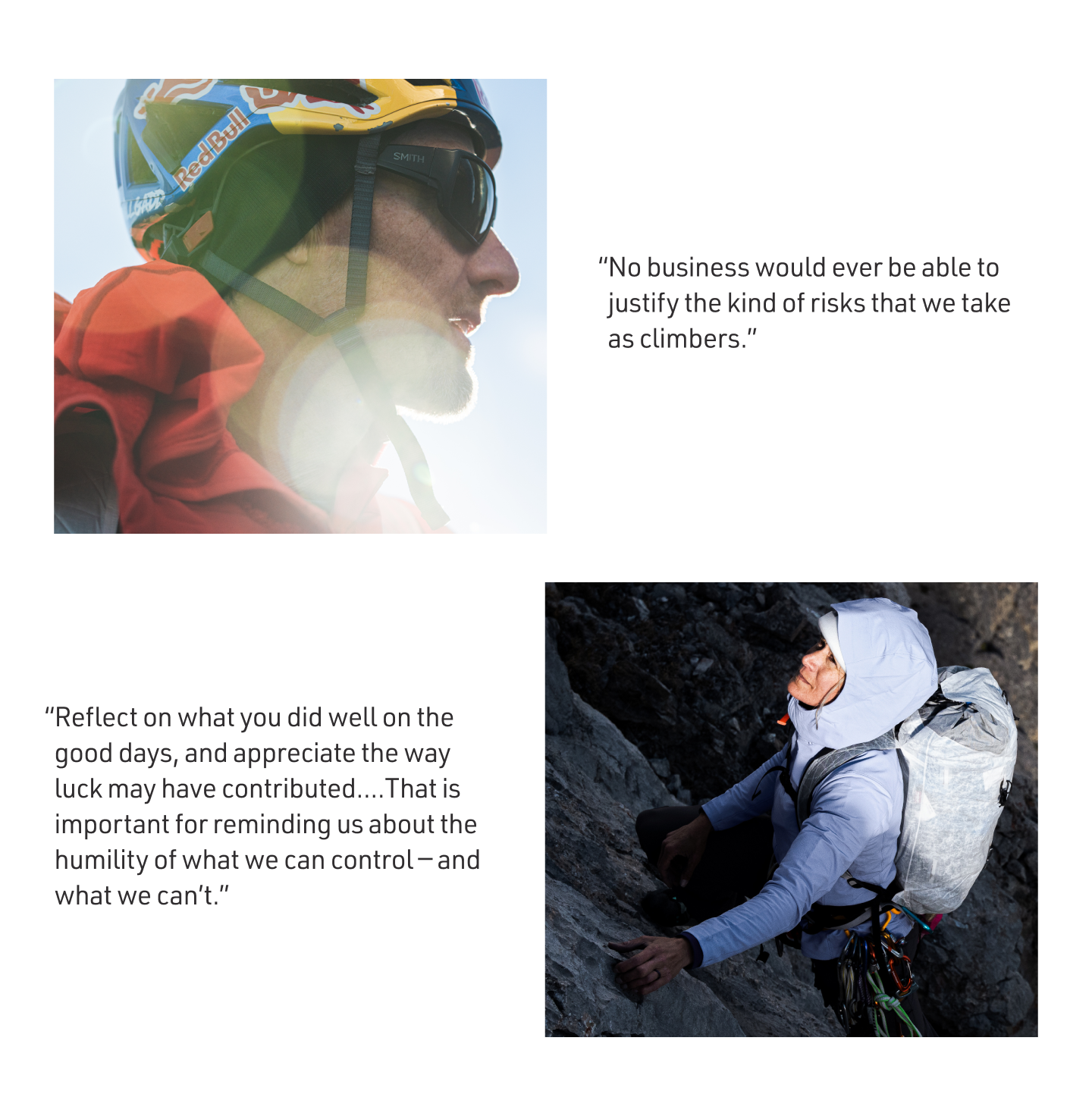

“No business would ever be able to justify the kind of risks that we take as climbers,” Will says.

Risk, of course, is a highly context-dependent term. The risks taken by a hedge-fund manager, for example, are categorically different than those faced by mountain athletes, where the consequences are measured in lives lost. But whether you’re Warren Buffet putting together a new portfolio or an alpinist forging their way up a new route, both are operating in a complicated, uncertain environment that can’t be perfectly controlled.

“Everyone thinks they have the secret sauce for staying safe,” he says. “Climbers like to say that they’re just as likely to die in a car accident as up on a cliff. This is frankly just bullshit. The number of people I know who’ve died in the mountains is huge compared to those who’ve been in car accidents.”

Risk vs. Danger

Risk is commonly, albeit incorrectly, used synonymously with danger. Risk, however, is danger plus uncertainty. For example, being 150 metres up a sheer vertical wall is an objectively dangerous situation. But if the climbers are competent, and if the route is safely protected with gear, and no obvious environmental hazards (such as a cornice) are present, then the risk of doing such a climb may be considered relatively low.

Sarah Hueniken is best known as the first North American woman to achieve the difficulty ratings of M11, M12, M13, and M14 in mixed climbing. Along with Will, she was also part of the first ascent of Niagara Falls, and she has led numerous first ascents of long alpine ice routes around the world. But perhaps her more important contributions to climbing are found in her guiding work, which has introduced countless women to ice and alpine climbing — disciplines that have historically lacked female representation.

Sarah knows first-hand how misleading the term “low risk” can be. In March 2019, a group of ice-climbing students were hit by an avalanche at the base of the popular Massey’s ice climb in Field, British Columbia — despite the avalanche risk being rated as moderate to low that day.

One of the students, Sonja Johnson Findlater, sustained serious injuries and later died in the hospital. Sonja was a close friend of Sarah’s. (This story is fully told in the Arc’teryx feature film “Not Alone.”)

Though Sarah wasn’t technically part of Sonja’s group that day — she had guided a different climb in the same area earlier that morning — Sarah had helped organize the trip. She also participated in the rescue. The emotional toll and guilt of feeling partly responsible for this tragedy has remained with Sarah to this day.

“I’ve become less confident in my ability to say what the real risks are because of what I’ve experienced,” she says. “There’s an element of bad luck, and we can’t fill in this equation as nice and neatly as I thought. We use our judgment and experience as best we can, but we can still get it wrong.”

Finding Meaning Through Risk

Paul Slovic is an American psychologist and researcher, whose seminal studies on risk perception and decision-making earned him the Bower Award and Prize for Achievement in Science from the Franklin Institute. Among other insights, Slovic discovered that when people derive pleasure from something, they tend to view the associated risk level as being low. This is a big red flag for climbers, who ought to be aware that their passion for their sport potentially diminishes their ability to make the right decisions.

“We minimize the hazards when we find intense meaning in what we’re doing,” says Will. “What we do as climbers is really cool, but the law of gravity still applies.”

Studies have identified a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, personality, neurobiological, and environmental factors that influence our inclination to take risks — or avoid them. In general, research has shown that traits like sensation seeking and impulsivity are associated with a higher propensity for risk-taking, while traits like neuroticism and conscientiousness tend to promote risk aversion — and this remains true among “adventure enthusiasts.”

Researchers have also captured statistically notable gender differences in outdoor sports, with women generally perceiving higher levels of risk in mountaineering, and men being more likely to take risk in the outdoors.

The complex interplay of these different factors makes it difficult, if not impossible, for climbers to ever expect themselves to become perfectly rational actors. Still, Will and Sarah have found tips that have helped them think about risk more clearly.

“I tell people to expect change and get in the habit of verbalizing it,” says Will. “Just saying, ‘Oh, this snow slab seems different,’ normalizes the kind of communication that you need with your partner.”

Sarah agrees that practicing open communication is essential, and suggests debriefing your day, even when everything went well. “Ask yourself on the hike out, would you have done anything differently? You might learn little tidbits. Also, appreciate your good days. They’re not a given. Reflect on what you did well on the good days, and appreciate the way luck may have contributed to your success. I think that is important for reminding us about the humility of what we can control — and what we can’t.”

A Question of Worth

Because understanding risk is so fraught with complexity, we often default to intuition and our own subjective sensibilities. Often, the way we seem to make decisions comes down to one question: Is this climb worth it to me?

For Will and Sarah, it’s a question that continues to change day to day.

“There’s a huge reward — physically, mentally, and emotionally — in taking risk while climbing,” says Sarah, noting that it’s often a crucial piece in challenging yourself. “I like feeling as if I trusted my decision-making and my judgment. I enjoy seeing that I can do something hard. It transfers to other parts of my life.”

Her experience is bolstered by a study that reveals that these sports can offer huge psychological benefits such as enhanced mood, autonomy, resilience, and self-efficacy, providing people with a socially accepted way to satisfy their need for reward and prestige that is associated with risk-taking.

Still, Sarah’s approach in the mountains has changed. Although she’s never thought of herself as a particularly big risk taker, after that tragic day in 2019, she’s reticent not only to guide in avalanche terrain, but even enter it herself.

Will is a bit more fluid. “When I was younger, it was really clear that these mountain sports were worth it,” he says. “But 40 years later, I also see the downsides. I think wrestling with that question is at the essence of this. And you don’t need to always have the same answer. I don’t have the same answer now that I did when I was 22. It changes, and that’s OK. But the wrestling with the question is the important part.”

In other words, if you’re not considering risk by the day, by the moment…well, that’s the biggest risk you could take.

There’s a huge reward — physically, mentally, and emotionally — in taking risk while climbing... I like feeling as if I trusted my decision-making and my judgment. I enjoy seeing that I can do something hard. It transfers to other parts of my life.

There’s a huge reward — physically, mentally, and emotionally — in taking risk while climbing... I like feeling as if I trusted my decision-making and my judgment. I enjoy seeing that I can do something hard. It transfers to other parts of my life.

Coming to Terms

After returning from a successful ascent of The Alt Left on Mount Rundle, Will researched Sarah’s concern about the knot. It turned out that she was correct. Will learned that the knot in question, under a low static load, theoretically could, indeed, roll.

“It turned out I was wrong twice that day,” says Will. “First, I was wrong about my understanding of the gear. But more important, I was wrong in how I responded to Sarah. I should’ve been open to her safety concern. That’s really important because how you respond to one safety concern determines whether the next one gets brought up. And that next one could make all the difference.”

For both Will and Sarah, the real reward could never be captured by a single climb. It’s the longevity of the pursuit, of being able to experience a lifetime enjoying the mountains and holding onto the humility that they are lucky enough to be in such a position. To get to be climbers — for life — is a risk worth taking.