Wrangling the Coast

Bivied on the shoulder of Mount Queen Bess, Ange Percival was conflicted. Just a few hours earlier their team had backed off one of her most ambitious photo projects to date: an attempt at a first descent off the summit of one of the crown jewels of British Columbia’s Coast Range. But a vast expanse unraveled in front of her, and any regret was easily erased that evening. This was a sight she never could have imagined growing up on the beaches of Australia.

“I remember just thinking: the ice age is real,” recalls Percival.

But being there herself wasn’t enough—Percival wanted the world to feel this. The team made it off the mountain and back to civilization, but a question nagged at Percival.

“How can I take this range—1200 kilometres long, with only three roads across it—and show it to my Mom and Dad?”

That question would become a driving force in her work for the next 6 years.

The Coast Range is unlike any other mountain range in North America. Stretching up from the sidewalks of North Vancouver to the border of Alaska, the heart of the range is one of the few places one can stand and see only mountains. Shoulders of the range slope to the Pacific Ocean along its western boundary, and on its eastern side high, arid valleys unravel windswept and undulating grasslands for hundreds of kilometers. From its furthest reaches north all the way to its southern terminus it has provided sustenance and a place of belonging to indigenous peoples since time immemorial, and it welcomes visitors from one of Canada’s largest cities just minutes from their doorstep.

Given that geographic complexity and cultural abundance, there would be no easy solution to communicating what Percival felt that evening on Queen Bess. She might not have known the complexity of what she was seeing at the time, but having found her sense of belonging after moving to Whistler, BC, Percival felt propelled to share the icy introspection she could only find deep in the range. The main question was how to go about it.

“It wasn’t about comparing it to other places like the Himalaya or the Tetons. It was about showing how special this range was.” said Percival.

Six years and countless adventures across the globe later, Percival kicked off that process, striding into the offices of Reelwater Productions, a Squamish-based production company that specializes in documentary filmmaking. It was a cold December day, one that would typically find Bryan Smith, Reelwater’s founder, out exploring the mountains. But Smith knew this would be a meeting would be worth taking.

“She sat us down and said: I want to make a movie about the Coast Mountains. Do you think you could pitch me something back by next week?,” remembers Smith.

A transplant from Washington State, Smith fell in love with the Coast Range after moving to Canada in his early thirties. To Smith, the project was a dream job. The timing of the ask was less than ideal.

As they contemplated the project at their office, equally inspired and intimidated between stacks of National Geographics, camera gear, and DVD’s from past productions, they knew one thing: any film that would be successful in bringing to the big screen the feeling of frigid awe Percival felt would live and die on one thing— the characters.

It wasn’t about comparing it to other places like the Himalaya or the Tetons. It was about showing how special this range was

It wasn’t about comparing it to other places like the Himalaya or the Tetons. It was about showing how special this range was

Experts in high-angle-this-weather-fuckin-sucks video production, co-directors Cam Sylvester and Smith have a deep history of balancing technical skill in the outdoors with an equal aptitude to connect with their subjects on a personal level. As the team embarked on a journey of uncovering poignant stories that would encapsulate the dynamism of a range—stories that dove into the ocean, pierced the sky, and was chock full of biodiversity best described by David Attenborough—they quickly realized that the remote, difficult to access characteristics of the range epitomized the characters they needed. These people only existed in their imagination, and to find the right people to represent such a complex range was going to be hard, but this was a challenge they liked. With that, Percival, Smith, and Sylvester began to scour every corner of the range.

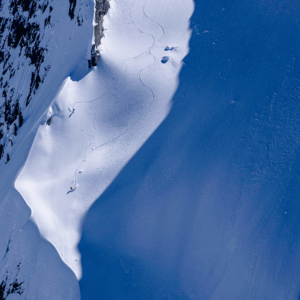

They first struck gold with Joe Lax, a snowboarder who had etched his signature on the range silently, going largely unnoticed (even by his sponsors at times) until Percival identified him as a symbolic character of snowboard mountaineering based out of Pemberton, British Columbia. Lax had been doing his thing so discreetly that even Sylvester and Smith, two avid riders who lived just down the road, barely knew him. Nonetheless, the trio embarked on a winter of pre-dawn starts and misadventures to better understand Lax’s backyard, but more importantly how that land shaped him.

The team identified Julia Niles and her climbing partner Lisa Van Sciver as two women steeped in mountaineering experience able to tackle a grand objective in the range, but also offering something else. Both are mothers, which would give the viewers a glimpse into the difficult task of balancing life in the mountains with family and real responsibility — a lived experience for those in the urban environments that butt up against the unbridled access in the Coast Range.

Ryan Oakden and his partner Kalissa Lolos chose a different path when they moved from Whistler to the remote community of Bralorne. On the other end of the urban-wildlife interface of the Coast Range, their move resonated with Percival, Smith and Sylvester, representing the desire for the off-the-beaten-path lifestyle that is just as much a calling card for the Coast Range as anything—the ability to get remote, and stay remote.

It wasn’t until deep in production that Percival found the final, crucial part of the story. Back in the Waddington Range, but this time 8 months’ pregnant hanging out the window of a helicopter shooting aerial photos, Percival had caught the ear of Mike King of White Saddle air.

“We had been trying to understand how we could bring the indigenous peoples of the range into this story, as we knew they were such an integral part—but finding a community tied to mountains was where we were getting stuck,” said Percival.

King, a gruff, down-to-business pilot in the area, seemed to take to Percival’s unyielding dedication to the range. Perhaps it was flying doors-off high above some of the biggest mountains in British Columbia in -15 degree Celsius at 8 months pregnant that convinced him. Or maybe, having spent multiple decades in the range, he had a soft spot for the story they were trying to tell. Regardless of how he got there, King was lined up to do food drops for a group of men from the Xeni Gwe’tin First Nation , and he saw the potential.

“You have to meet Jimmy. Let’s call him right now”, King told Percival.

Just a phone call later, the 37-year-old Chief Jimmy Lulua of the Xeni Gwe’tin First Nation was on board.

Lulua was leading a group of men on a traverse their people had been doing for hundreds of years but had in recent time lost touch with the tradition. Starting at Chilko Lake at the western border of the Waddington Range and at the heart of their traditional territory the team would gain the steep forested slopes of the Waddington Range, navigate the glaciers and icefields, and descend thousands of meters to the Bute Inlet, home to the traditional territory of the Homathko First Nation. Percival, Smith, and Sylvester knew within just a few minutes of hearing Lulua’s story and his goals as Chief of the Nemiah Valley-based people’s, this was the final, and most crucial piece to telling the story of the Coast Range.

When Smith and Sylvester were able to finally turn around that pitch that Percival requested on the cold, December day, their 15-page PDF was remarkably close to what the final product would end up being. It outlined an ode to the characters who were shaped by the Coast Range, and what made the range so unique. What they didn’t realize was that in searching for those characters and identifying the unifying theme of the film as long hours in in the editing process turned into weeks, was that those characters were a reflection of themselves.

“I hadn’t really thought about how much the Coast Range had shaped me until I started thinking about this as a film,” said Percival.

While no digital experience can do justice to the lived experience of thousands of years on the land, a steep turn on a fifty-five-degree slope, or the joy of teaching your kid to love an environment the way you do, Shaped by Wild comes close.

Now the film just needs to make its way to Sydney, Australia for Percival’s parents to begin to fathom what made their daughter stray so far from the beach.

I hadn’t really thought about how much the Coast Range had shaped me until I started thinking about this as a film

I hadn’t really thought about how much the Coast Range had shaped me until I started thinking about this as a film